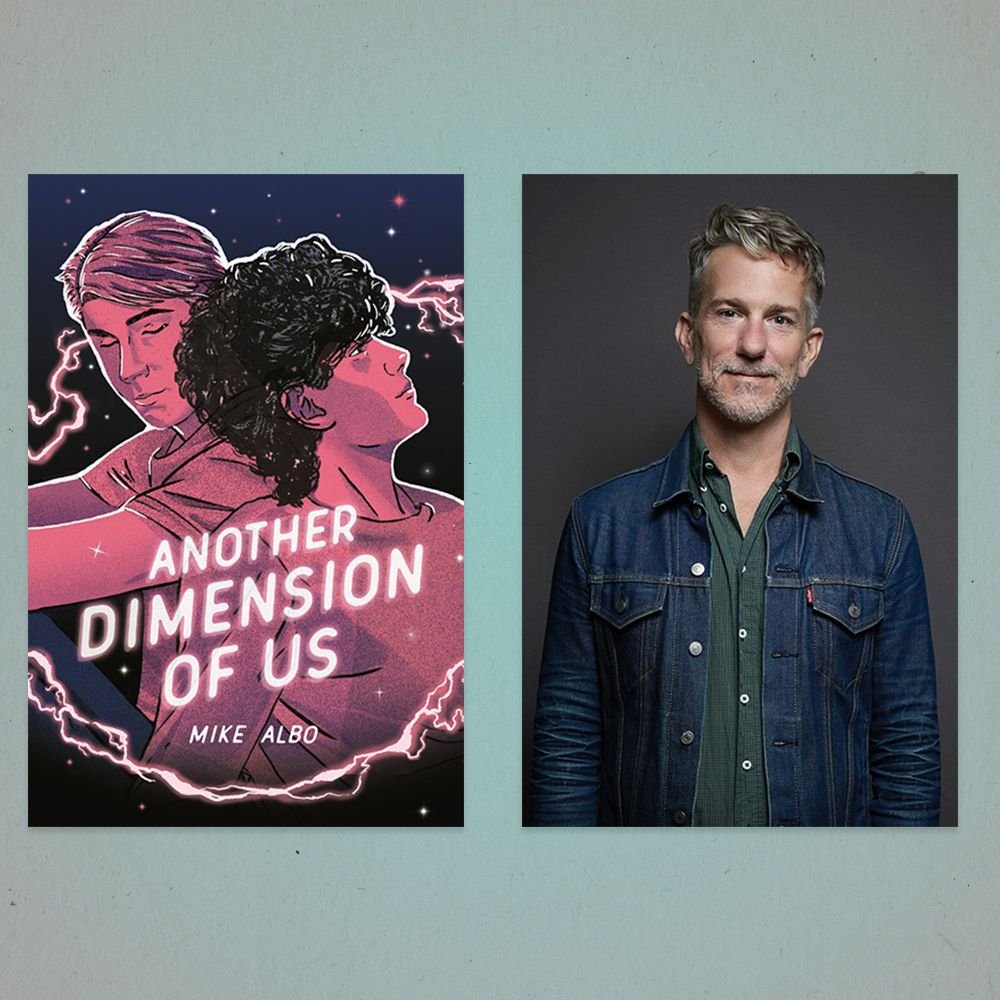

With “Another Dimension of Us,” Albo makes a transcendent contribution to YA queer lit.

If you’ve never heard of Mike Albo before, now’s the time to add his name to your must-read list. As a writer, he’s kind of done it all: He’s written a gay coming-of-age novel called Hornito, as well as the somewhat fictionalized self-helper The Underminer: The Best Friend Who Casually Destroys Your Life (co-written with his pal Virginia Heffernan). Each work is scaffolded by Albo’s pithy humor and insightful observations about what makes us tick. Albo has also been published in The New Yorker, New York Magazine, GQ, Departures, W Magazine, TED, Elle Decor, and numerous other magazines and websites. He even once penned a horoscope column and a love advice column, and was the “Critical Shopper” columnist for The New York Times.

Albo also gives us comedic works live — which has led him on tours all over the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and Europe — and has mounted a couple of solo shows, including Spermhood: Diary of a Donor and The Junket, which ran Off Broadway. He is also a part of the long-running comedy trio Unitard and the legendary (“in their own minds,” according to his website) dance collective the Dazzle Dancers, and his charm has seen him in the role of emcee for organizations like Yaddo, La Mama, Visual AIDS, and The Moth, for which he was one of the original hosts.

Yet, despite so many accolades, Albo tells Shondaland his first and most enduring love is poetry. One only needs to read his latest work, a YA-ish novel called Another Dimension of Us, for evidence. The book, interwoven with both prose and poetry, is a love story that transcends time and space (quite literally) with interplaying themes of young love, longing, social ostracization, friendship, loyalty, and astral projection as a group of friends (and even a couple of supportive adults) in 1986 and in 2044 find and help save one another in unexpected, wild circumstances.

Albo spoke with Shondaland about the process and inspiration behind writing Another Dimension of Us, and what he’d travel back in time to tell his teenage self.

VIVIAN MANNING-SCHAFFEL: What inspired Another Dimension of Us?

MIKE ALBO: I have been collecting new-age books for a long time. Every time I go out to L.A., I used to go to the Bodhi Tree bookstore, may it rest in peace or in the astral plane somewhere. Over the years, I collected these new-age titles for their kitsch value but also because I am kind of into them, you know? There was this one book called The Art and Practice of Astral Projection by Ophiel, which I also mention in the acknowledgments, and I’ve always held on to that book. Over the past years, I’ve been like, “Oh, it’d be interesting to do something with it,” just to fictionalize it — I had this whole sort of path of fictionalizing other ones too. But with that one, I thought, “What if these kids find the book?” I always feel like books are so powerful themselves, so I sort of started with that idea, and then the characters kind of jumped out for me.

Another Dimension of Us

VMS: When you’re looking outside the window and have nothing else to do, astral projection seems like a great way out, right?

MA: Totally! It really helped me tap into my 14-, 15-year-old self because, I think for a lot of us who grew up queer, I spent a lot of time alone in my room. When society tells you to stay inside because there’s a pandemic, I’m like, “Great, I get to listen to Kate Bush and write poetry. No problem, I’ve been there.” So, it really kind of helped me tap into that state of mind that I came from, if that makes any sense.

VMS: Listening to Kate Bush always sounds good to me too. How did you know you wanted to write a book focused on queer YA literature?

MA: There’s a practical side. I had an in with Francesco [Sedita, president and publisher at Penguin Workshop] and his colleague. He wanted to work with me and always wanted me to write some sort of young adult book. So, I kind of had that in my mind, you know what I mean? To me, it’s all drag. YA is a genre created by the publishing industry, and as much as I’m really excited to be part of that industry, I just felt these characters should be young, and I felt the story pretty deeply. It came to me pretty emotionally and urgently.

VMS: You can feel that in the rendering of these characters, places, and their experiences. It’s a love story that transcends space and time. We are living in a time when we ask ourselves, how the hell were we ever supposed to know that so little would change in parts of this country, right? It feels like contributions to this genre are more important than ever.

MA: It’s pretty bizarre because I think even from when I started working on it until now, book banning hadn’t reached the height as an issue as it has now, do you know what I mean? I was finishing this up when “Don’t Say Gay” happened, and there were segments of the population attacking people because of drag shows and hounding librarians. I’m very curious, to be honest, how this will play out. So far, I haven’t had any problems. I’m going down to Virginia, my home state, to hang out with my high school and go to a couple of high school classes. I want to go to as many libraries as possible and as many classrooms as possible and try to encourage kids to feel their feelings and write them down. I grew up outside of D.C. in this town called Springfield, a very typical suburban town — my parents are still there, and my family is still there. It was sort of easy to explore the idea of what it would look like in 2044 because it’s changed so much since when I was a kid. It feels very supernatural and gothic, even just mainly for historical events — Virginia is just a very bloody state in terms of slavery and civil war. I wanted to sort of explore that a little bit.

VMS: Through this amalgam of characters, you’re able to artfully connect what it meant to be queer when we were growing up with what gender identity might look like 20 years from now. You can’t go back to showing what queer life was like in the 1980s without getting into the AIDS crisis and how it affected us all, which you do through the character Sally. There’s a mindfulness toward imparting our experience to younger readers. Is that something that was deliberate for you?

MA: Oh, thank you so much! I do. I don’t think the right way to do it is to be like, “In my day, we walked five miles through snow and were scared of AIDS,” but I think there’s a sort of overarching theme that emerged about the power of history. I think there’s a sort of overarching theme of people feeling the same feelings throughout history and throughout time, and to learn empathy for others in the past, not just others in your present, is kind of important. So, I sort of hope that it will help contemporary 15-year-olds be like, “Wow, someone back then was feeling those feelings, feeling what I’m feeling.”

VMS: Was it fun or challenging to imagine what life might look like for people in 20 years?

MA: It was fun. I had a little bit of training because I’ve been working on a science fiction book for about 15 years and finished it. Hopefully, this book will help that book get printed somewhere. I did a lot of practice with world-building through that other work, so my chops are a little bit more confident. It’s really hard to world-build, but I think I at least had a little bit more confidence in doing it.

VMS: Did you know when you started writing the book that it would be about two different generations? Did you outline that, or was that something that just kind of came to you in the process of writing it?

MA: This is going to sound as occult as the subject, so I don’t want to make it sound too magical, but some of those characters came to me pretty easily. I knew I had to write about a girl in the future who was ostracized for the way she looked. I think I had in my mind there’s a person in the future who meets this boy. I didn’t really know how that ending was going to happen until I was midway through writing it. I had to tell myself all the time to just sit down and write it, you know what I mean?

VMS: You also include a character who is a nod to commercialism.

MA: I’m sort of obsessed with commercialism and consumerism. All my previous work, whether it’s been comedy or other books, it’s always been my obsession — commercials and jingles and advertisements and the language of it. Just the way that it’s this gas in our air we are constantly breathing. I knew I had to make the astral plane less mystical and more polluted.

VMS: That’s a really good way of putting it! I feel like these things live in your subconscious all the time, and that device kind of keeps the reader grounded. When Pris tells Tommy that people don’t use the term LGBTQI anymore and that people just define their gender and identity for themselves, isn’t that utopia?

MA: It’s funny. I want to say that it seemed even more hopeful three years ago when I began working on this. Like, as we were talking about book banning, the sort of blowback against freedom of gender expression has been pretty radical. One way that I walked into the book was I talked to my niece and my nephew and young people about what high school is like for them now, because I had this hunch that no matter how acceptable people are made, there’s always going to be those who are popular, there’s always going to be outcasts, and there’s always going to be people who are made to feel bad about themselves. It’s just human nature, in a way. So, one of my challenges was like, how are kids unpopular in 2044? Who are the outcasts? What are they like? I worked hard to try to make Pris’ feelings of being alone genuine, and her feelings of watching her best friend find their look — you could tell Jayde’s going to become a huge success. Pris feels Jayde pulling away, and I feel like that is such a timeless thing that happens to teenagers.

I feel like my Michelle Obama platform about this book is how important it is to have a private place to write down your feelings and your thoughts with handwriting in a physical book — not on any kind of electronic thing and not something that you’re going to post.

VMS: This whole other metaphor that you kind of work in there about transcending your physical body, which was so vital to those during the AIDS crisis as well as to people now — how did you work through the details of that?

MA: There’s something that I wanted to explore, the fact that Tommy has bad acne, Pris has striped skin, and Dara has this sort of where are you from? I-can’t-place-your-race skin. I had this idea that these kids who are dealing with surfaces, or their bodies, and how they’re being looked at, that helps them to understand how to transcend your body, and also to start exploring the idea that we’re spirits in physical form, having a human experience. Astral projection is all about that, so I guess that’s what I’m saying.

VMS: It broke my heart when Tommy said his acne was like love that had nowhere to go.

MA: That was my experience. I had very bad skin when I was a teenager, and it was happening at the same time [I was] coming to admit to myself that I was gay. In some ways, I can’t tell which affected my life more. It was like the outward version of what was happening inside. I really hope that kids going through skin issues, that this resonates with them. That does really affect your mental health, and it’s not really talked about that much.

VMS: Let’s get into the wordsmithing part of the book. I feel like you had a really good time referencing poets and playing with words. Did you have so much fun writing about writing? What went into those conscious choices about the poets whom you quoted?

MA: Being in a pandemic in your apartment, I have this book of poems by Anne Sexton, I have a book of poems by Anna Akhmatova here. … I just sort of reached out and picked up books that were around. I’ve always been a poet first; it’s my first love. What’s a more beautiful, romantic character than a beautiful boy who writes poetry? I actually wanted to put so much more poetry in it, but with copyright law, there’s a little bit of an obstacle to getting more poets in there. So, a lot of poets I just sort of name-check. I could have thrown in hundreds of names and found more quotes if I wanted to, but that would have been a different book, I suppose. Unfortunately, a lot of the poets I quote are public domain, and a lot of those poets are white men, so I had to work with what I had.

VMS: If you could go back to when you were Tommy, René, and Dara’s age and give yourself one piece of advice, what would you tell yourself?

MA: I think it would be to say, “Express your feelings to your friends, and good for you for expressing your feelings through writing.” I’m very proud of all three of them for keeping notebooks, and I would encourage them to keep doing that. I feel like my Michelle Obama platform about this book is how important it is to have a private place to write down your feelings and your thoughts with handwriting in a physical book — not on any kind of electronic thing and not something that you’re going to post. It’s so important to create an inner life, and one of the ways to create an inner life is to write down your feelings for yourself and no one else.

VMS: Regarding other parts of your craft, do you think you’ll return to the stage at any point soon?

MA: That’s so nice! I’m hoping to. I’m in talks with a very nice editor who was offering to maybe do an audio version of my work, so it would be something you would listen to on Spotify or something. I’ve been putting together a big collection of stuff that I’ve been doing since 1997 and seeing what could still resonate. But I think that might bring me back to the stage as well to do a work that’s maybe old and new stuff.